Merrick's Leviathan

A revamped short story I wrote in the summer of 2019

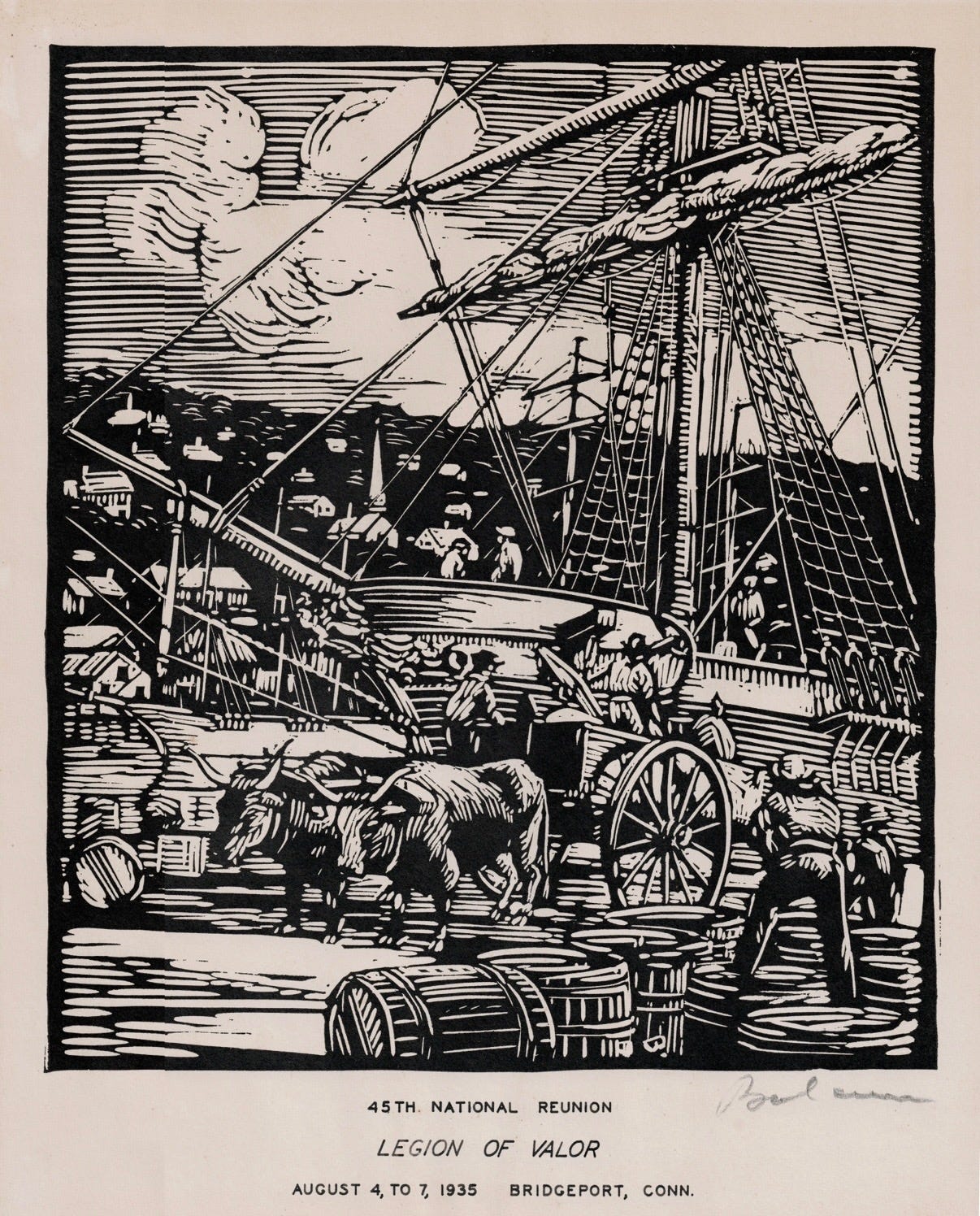

I wrote this story in the summer of 2019, at the conclusion of a class I took on the campus of Boston College. At the time (key words), I thought it was excellent. Over six years later, I have revisited the story, made countless tiny edits, and added some images from my archive which fit the feeling I was going for. Perfect? No, but a helluva lot more refined. So sit back, relax, and enjoy a rare piece of fiction published to this Substack.

I.

To paraphrase Melville, call me Seamus. I write to you from somewhere I’ve christened ‘Purgatory on Earth,’ a little place to spend idle in my ever-draining years on this mortal coil. Yes, I’ve found purgatory: a town by the name of Merrick, Connecticut, a pearl of a U.S.A. whose glory days lie far in her past. I commence the authorship of this account in 1979, approaching my eighth decade of life, for I was born on the final day of 1899.

I stand apart from most folks, always have. The nouveau riche Merrick of today is home to mansions utilized by the wealthy on their summer excursions and little else. In the summer, the population is, from what I estimate, 7,500. In the winter, people here drop to round-about a tenth of that. I never understood such a fascination people who ‘summer’ here have with ostentation, with spending, with letting people know of your success. I’ve always kept to myself in my seventy-nine years, and especially for the last forty-four I’ve lived here. A native I am not: I hail from Scotland, and seem to owe my gruff mannerisms and down-the-middle outlook to my ancestry.

McCready be my name, one which ends with me. My bloodline has flowed since the 1460s, if my late father and his are to be believed. When I resided in Scotland, during my ever-receding youth, I served as deckhand on many a fishing excursion. As my teen years elapsed, my body, so used to punishing roles at sea, adjusted to the always-shifting waves over static ground, and to the skies of storms and cold over the fair weather and shining sun so many here in Merrick strive to stay beneath. Modern folk of the United States, pah! By and large I despise them. They are too often ones to talk, to overly confide in all people they meet.

Very, very rarely do I go to town; when I do, I speak as little as possible. Why try to make new friends at my age, when, by my best estimates, I shall perish in under one thousand days? I have no relatives — at least, none I know of; no friends, as I made clear; and, though I was married for some time, my lovely woman perished some years ago. Cancer is a mysterious beast.

We were too frugal (and, I suppose, suspicious) to attend a doctor’s visit annually. My gal and I survived on remedies of rest, boiled water, and the medical injections we would allow ourselves to receive every five years. Dental work was a luxury we both decided not to indulge in; this was fine, as I never once recall consuming sugar. I have lived alone for eight years now, though at my age, it has felt more like eight months. The day I laid my wife to rest seemed to be a moment ago; I vividly recall lowering her coffin into the plot I had dug on our property, without any tears falling to stain the wood.

Insensitive? I thought not; we must meet our final day some time, after all.

I have had this resolute outlook since I was but a lad. At the age of seventeen, my father passed at the age of fifty-six. He fell to gangrene, though the disease was not common in our area. He requested a burial at sea, and I was the one who dumped him to his fate, feet sewn. It was a solemn event, to be sure, but I do not recall having any emotional outburst, no uncontrollable salt that fell from my eyes. I tossed the crudely-made box containing him into the waves before reading a biblical passage to a small gathering, and that was that. I never felt any true sadness after his days came to an end, though we had spent months together on the high seas.

Before that, of course, I had completed primary school, I joined the ranks of my father’s fishing ship, the Iron Tusk. I was merely twelve at the time, yet my family believed my six years of education was enough. Iron Tusk was a lovely ship. She was named after an elephant’s tusk, coated in iron, presented to my father as a gift from a strange gent he once knew. The man — I cannot recall his name — was an explorer, who recovered the item somewhere deep in the Congo. He had the iron plating done and the item sent to my father as a thank-you for financing one of his expeditions. The tusk became a heirloom; I gaze upon it now as I write this.

Yes, my family was wealthy, but we lived in a modest fashion. Our house was average in description, and most of our wealth was buried on our land, untouched. We never spoke of our riches, much less used them. Perhaps that’s why I’m so irate that people in Merrick tend to flaunt proof of their profits.

Why Merrick? Dear reader, most days I ask myself this; the simple truth was that there was nowhere else to be. Shortly after my father died, my mother passed at forty-one, partially of grief — all of this in my eighteenth year. As I was the sole next of kin, I found myself alone, without even a solitary elder. My only uncle died when I was but five years of age. I had, like I have now, no one to call ‘friend’ or ‘ally.’

Yet Seamus, you may be thinking, this was seventeen years before you left for Merrick! Well, I spent that time being a lowly drifter. I traveled to various ports, receiving brief occupations on fishing ships and earning compliments from the crew for possessing such a skill level at an age like mine.

I survived exclusively off of my maritime earnings. I put my money into replacing the tattered clothes on my back with newer iterations, mediocre food (though I always treated myself to a single upper-class meal on shore leave), and rooms at seedy hotels. This continued for over a decade and a half. In all honesty, I did not have to do this, as I knew where my parent’s wealth lay in the family acres spread across the north of Scotland. My main reason for this time spent at sea was that, though I debated whether there was a God, I felt that my dad was watching above me in some form. He would be furious if I forever lived off of money I did not earn.

I considered seventeen years long enough engaging in this tiresome, yet humbling pursuit. In 1935, I finally took my savings back to Scotland and dragged my battered body up to my family’s land. After collecting the McCready riches through several days of digging, I sold the land within the month to a hunting company for what would have been two years’ salary for my father in a good year. I used part of it to buy a small lorry, which I loaded with everything to the McCready name. I had decided Scotland was no longer for me, and so I drove down to London — where, after selling the lorry, I bought a second-class ticket on a ship for New York City.

Having landed safely at Ellis Island, I made the decision to rest my life somewhere shrouded in relative secrecy, with the only people living there like-minded as I. I had only worked twenty-three years, but I felt that my father would be satisfied with the drifter’s life I wore out over the high seas. I spent around a month in New York, carrying my wealth in two trunks, in the back of another lorry I had purchased cheaply. I appeared poor, and none I encountered assumed my chests were full of wealth they could not comprehend.

I glided around in the lesser parts of town to maintain this facade, asking each hotel clerk I encountered if they knew of a quiet seaside village where an old man might swoon over life’s perfection. None of the descriptions they offered satisfied me; Massachusetts seemed to be the one constant in their answers. I, myself, fancied Connecticut a little more — I found those I met from Massachusetts to be quite arrogant.

One day, at the fifth or sixth establishment I patronized, the name of Merrick arose: this was a small township, tucked in the southeastern corner of the state, near the Rhode Island border. Right upon the edge of the Long Island Sound, the mouth of which opens into the Atlantic. It was thus settled; I would go to Merrick the next day.

On my drive to Merrick, I passed several towns, some of which I briefly stopped in. Greenwich and Darien struck me as far too upper-class and flashy for my liking; Bridgeport, too industrial and grimy.

When I did arrive in Merrick, I could not have been happier. The town held 200 souls at most. I went to the courthouse and asked if there were any properties on the coastline for sale. The gentleman I talked to directed me to a real-estate agent in the neighboring town, who showed me just two residences in Merrick that were available — one a ranch house in the middle of town, the other an isolated cottage, on perhaps an acre of land which jutted out slightly into the water. I sprung for the latter; a deal was made at $2,750.

I located the place and made myself at home with my surroundings. As you may expect, I buried most of my family’s fortune on the grounds, with the hope of living modestly for the remainder of my days. It was at this time that I dubbed the cottage White Whale, in honor of Moby-Dick, a book my father gave me when I was but a boy. I still have the very copy in my possession.

My soul was quite happy to drift alone, but sentiments are always subject to change.

In late 1945, as I got set to mark my first decade at White Whale, I went into town, on one of my rare trips off of my property. The aim, that particular day, was simple: fetch some firewood and other provisions, ideally without much social interaction. While I was collecting my goods in the corner store, I saw a young woman at the counter. Now, reader, I don’t believe in the superficial, instant sort of appreciation, but I grew infatuated with the lass the moment I saw her.

I bought my goods and went across the street to have lunch at the only eatery in town, keeping an eye on the door all the while. After a half-hour or so had elapsed, she left the shop and walked across the street. By fate, she strolled into the restaurant. The place was devoid of patrons save for her and I; perhaps unsurprisingly, she asked to sit next to me, a proposition I accepted.

She introduced herself as Mason Dailor. A weathered, golden tint seemed to surround her as her name escaped her lips, forming a timeless beauty which belied her age: twenty-two years, she told me. Ms. Dailor had recently lost her beau, who fought for the nation overseas in the Second World War. I expressed my sympathy before telling her a bit about my life: my Scottish upbringing and years on the sea, culminating in the loss of my parents within one year and resulting lack of family at eighteen, and my eventual move to New York City before finding Merrick.

Mason, like me, was an only child, though she once had a younger brother who perished in a house fire many years ago. Her parents lived on the other side of the nation, in California, and hadn’t spoken to her in quite some time. She found herself in Merrick around the same age I found myself without a family to trust in, and had been living here for four years with her old chap. He was a gentleman named John Page, and Mason had been taking residence in his family’s homestead. Page joined the war in 1943 and had been killed, she explained, in Europe late last year. She still lived with the Page family, having little to live for but her meager occupation as a clerk.

I felt awkward in asking, but I offered her my humble home as a place to live. I was twenty-three years her senior or thereabouts, but I was not looking for an ill-advised romance. Ms. Dailor simply seemed like a fine, respectable woman with traditional values like those of my ancestors, a trait I deeply admired her for. She told me to come back to the store she worked at in three days, where she would tell me her decision; I did so after these days elapsed, and lo! she accepted.

Alas, after moving her in, a problem arose: White Whale only had one bedroom, and I had one bed to my name. Perhaps if I were younger, I would not feel ashamed in asking a woman to share a bed with me; but at my age, and with my hairs of gray, I felt prudish and could not bring myself to ask her. “Maybe,” I told her, “we spoke too soon.” Mason, however, did not mind, and so we slept together without any form of intercourse taking place.

Months passed in which we lived together before some sort of relationship began to blossom, rooted in commonality. I had a hobby of painting the water whenever a storm was brewing, and she, by my side, would do the same, producing a depiction far better than I could ever render. I smoked as dusk began to settle each night; routinely, she would request a few inhales of my pipe, which I always topped up with vanilla tobacco.

As I mused, calmly gazing over the inlet before my cottage, she, too, indulged in these quiet moments. It had become apparent to me that we were more similar than I first realized.

We were wed ten months after we met, in 1946. The Page family were the only three in attendance. Make no mistake, this was not an extravagant affair. I had yet to tell Mason, now Mason Dailor McCready, about the wealth I had buried on my land. The only valuable item I displayed in my cabin was the Iron Tusk which, I figured, was worth $500 or more to the right person.

The wedding was a fine affair. Page’s family was satisfied that Mason had found someone to live alongside, though they expressed some reservation at our twenty-three year age difference. I felt that this was, in fact, for the better; had I been younger and more reckless, I may have led her down an unfortunate path. The wedding concluded with little fanfare, with Mason and I vowing not to have children enter our lives.

Our marriage’s consummation was the first true pleasure I had ever experienced: a little spark fell upon my ocean-drenched heart. The day after this had occurred, I revealed to her the full extent of my family’s wealth, and a mission I vowed to undertake.

You see, my father left me a map before he had passed, illustrating the whereabouts of a ship, the Tungsten Hound, for which he was a crew member. She sunk in 1902, around 150 miles off of Portugal. Her cargo hold was filled with rare mementos and valuables, the likes of which were said to be valued at over three-quarter million United States dollars. He gave me this map in the hopes that I would find her treasure before I passed.

I dismissed the story, initially, as mere pirate fantasy, the kind found in children’s literature. Even so, part of me felt that the bounty was worth seeking. I’ve always wanted to have pride in death, and that would be a proud moment.

After I had talked Mason through my existing wealth (and the subsequent shock had subsided), I declared that we should undertake this journey one day later in our lives. She seemed hesitant at first before, several days later, telling me that the idea was one which held promise. She suggested we go out later that very month and rent a ship for the mission, but I told her this was going at the meat too soon. We must wait, I said, for you to grow older.

As we did, Mason and I continued the McCready way of modesty. Our only indulgence became a 1957 Chevrolet Corvette, a brand-new extravagance which Mason bought, feeling it was a shot of American adrenaline far outclassing the old, cheap lorry I had kept for years. This purchase, though, was tame compared to those made by the people who had begun to vacation in Merrick over the elapsing summers. Extravagant boats and vehicles dotted the village in the dog days, much to my chagrin. As time slipped through the hour-glass, I grew more and more weary of those in town during these periods — as did Mason, who continued to adopt more and more of my mannerisms. Our joyful, subtle matrimony saw us becoming ever closer to the same person. Neither of us would have guessed that fate’s hand had been pushing our union towards its demise.

In 1969, on one of our twice-a-decade doctor’s visits, Mason was pulled aside by the physician after we received our injections. Cold minutes went by as I sat outside in the waiting-room. Eventually, she emerged with a grim look clouding her complexion. The news was for the worse: Mason had a form of cancer. The doctor offered to help fend off this disease in any way he could, but both my wife and I felt it would be better to let her slip into the Garden of the Gods naturally. As I had maintained for a lifetime, all must have their final moment, no matter how soon it may seem to be.

On the first of May, 1971, Mason Dailor McCready was laid to rest. She had lived forty-seven years. I was seventy-one. As her family had lost contact with us many years ago, no witnesses were present. A storm was gathering as I covered the coffin (I asked if she had wanted a land or sea burial; she requested land) and erected the simple tombstone I had carved. I read a brief biblical passage out loud after this was done, and went inside to light the fire as the first rains fell.

I was a monolith yet again. My sadness was negligible, but I did feel some regret: our treasure-hunting adventure, which we had long spoken of, had never become reality. The proposition hovered in our minds for years, as the days passed like mere seconds, as the years were over in an hour’s time. As I write this, reader, I am proud to say that I have purchased a sizable trawler, resting in a harbor a few miles away, and I plan on seizing the opportunity as I reach the sunset of my life.

II.

A.

I set out alone. My plan involves hiring a crew in Portugal, who will help me dive down into the wreckage and recover the valuables I have spoken of. I took nothing from Merrick besides the essentials, save for the Iron Tusk as a bit of luck. As I boarded my vessel, my wife’s memory by my side, I left the harbor and felt something I had never experienced in my near-complete lifetime: tears escaping my weathered eyes. I could only describe such an event as years of repressed, unmarked anguish rising to a superficial climax.

Throughout my voyage, the seas take the form of an aquamarine carpet unraveling before me, smooth and full of promise.

B.

The landing in Portugal after days of uneventful travel requires no real disclosure, so serene were the waters. The vibrant port filled me with a newfound gusto and eagerness to locate the spoils as soon as I disembarked.

In short order, the crew was found and prepared: off-duty sailors in their twenties and thirties, eight and ten of them, were willing and able to set out towards the location marked on the map.

Once again, I do not find a need to pen any harrowing description for you to pore over. The men and I arrived at the coordinates within a day’s travel. The cerulean waters seem paved — still as smooth as one could hope.

C.

As the dive commenced, I stayed aboard ship with four of the men. After just twenty minutes had elapsed, the divers announced they had found the wealths so spoken of, within the very wreckage my father had escaped seventy-seven years earlier. With a faint smile of satisfaction, I assumed a diving outfit and jumped into the depths. Several fathoms down, the wreck of the Tungsten Hound lay dormant, its insides torn open to reveal the treasures she held. Shortly after I surfaced, excavating began via the trawler’s crane. Sure, excitement filled me, but my eyes never once glittered with the glimmer of greed.

By nightfall, we had the treasure in full. To the shock of the men with me, I announced that I would not keep it for myself. I planned on leaving it to the town of Merrick, in order to establish a Museum of the High Seas, so to speak. I feel my father and wife would have been proud of such a monument, a form of legacy which would take the role of say, a Seamus, Jr.

We undertook the return trip, victorious if humdrum, after which I thanked and paid the men their share before setting off on the journey home.

D.

I could not stop imagining what was to be, the Dailor-McCready Museum of the High Seas. My vision seemed ideal. Though I would likely not live to see its completion, I would know that my life, as well as that of my father’s, would have been put into something worthy.

Halfway through my journey home, an ancient tempest formed above my boat, bringing steely skies and a sense of uneasiness. This was no ordinary storm cell; I could sense its vicious intentions from miles out. My soul filled with a primordial dread which I had not felt since I was a lad, cowering in fright the first time I had heard thunder. I knew this ship could handle it, but I could not shake the feeling that the end was nigh. As hell broke out over the sea, I felt the worst approaching. All of my years as a deck hand flashed before me; this squall had outclassed everything I had seen in that time.

My mind weighed the trawler’s chances against the churning waves when I heard a mighty explosion from below decks. Her engine was no more. Perhaps I should have been driven to panic, but I accepted this, reader, as fate. There was more than one lifeboat on the ship, but, being alone, I could only use one — and one was far too small for both me and the recovered treasure. Besides, hailing any form of rescue at the latitude and longitude I rested on was a fool’s errand.

A captain must go down with his ship, as the old saying goes, and so, walking out onto the sinking deck, I prepared to meet my end. Do not, however, feel sadness at the Museum of the High Seas escaping realization. As the freezing waters enveloped my feet, my right hand bound to the railing by thick, salted rope as a matter of self-imposed restraint, I felt a sense of glowing pride in my final moments, aided by the spirits I had drunk.

This was all I ever wanted…

III.

Joseph Merrick was the true name of the Elephant Man, a mysterious medical case the likes of whom I have admired since I was relayed his unfortunate tale by a shipmate in my second decade of life. I find it quite a coincidence that I came to rest in a town given his very name. Perhaps it was dubbed thus in his memory, though my wishful thinking is often untrue. I write these words in his honor, and as I see my wife dying on the bedside beside me. I leave this note with a bit of roughly-written Latin prose, the likes of which I hope to be placed on my epitaph:

Sit somnia nostra habetur.

Non enim potest fieri male intellectas. Ut moriamur superbia.

Humbly,

- Seamus McCready, the 30th of April 1971

I LOVE this so much!!! Fact and fiction, cars and music … what can’t you write about?

Holy smokes I loved reading some Tyler fiction. Very very cool my friend ❤️